R500.00

For Newman, the ideal university is a community of thinkers, engaging in intellectual pursuits not for any external purpose, but as an end in itself. Envisaging a broad, liberal education, which teaches students “to think and to reason and to compare and to discriminate and to analyse”, Newman held that narrow minds were born of narrow specialisation and stipulated that students should be given a solid grounding in all areas of study. A restricted, vocational education was out of the question for him. Somewhat surprisingly, he also espoused the view that universities should be entirely free of religious interference, putting forward a secular, pluralist and inclusive ideal.

In its championing of a truly well-rounded education, this is a sympathetic vision, but there are some fundamental problems with Newman’s ideas. Despite his vision of a secular university, for Newman “religious truth is not only a portion, but a condition of general knowledge. To blot it out is nothing short … of unravelling the web of university teaching”. Knowledge alone cannot improve the individual – God, who sustains all truth, is a requirement, and this is an idea that alienates many readers.

Showing his preoccupation with man’s fallen nature, Newman wrote: “Quarry the granite rock with razors, or moor the vessel with a thread of silk; then may you hope with such keen and delicate instruments as human knowledge and human reason to contend against those giants, the passion and the pride of man.” This is an unattractively pessimistic view of humankind’s capacity for self-improvement.

Perhaps the ultimate problem with The Idea is its sheer anti-utilitarianism. Writing at a time when only an elite benefited from a university education, Newman could not have conceived of a situation where over 2 million people are enrolled at British universities and places are heavily oversubscribed. Newman says little about the level of practical, employable skills that should be imparted as part of a course of higher education, revealing his limitations as the ultimate ivory tower-dweller. He offers us little help on how the balance can be struck between pursuing knowledge for its own sake and giving students the salable skills they surely deserve. He has even less to offer on the pressing matter of how the whole enterprise may be paid for.

Newman’s approach is indeed dated, yet his articulation of the power of a university education to develop the individual in ways that far exceed the narrow limits of academic ability remains striking. Above all, Newman was arguing that the primary role of the university was to give students a “perfection of the intellect … the clear, calm, accurate vision and comprehension of all things” that allows the individual to make good judgments. He wrote of this: “It is almost prophetic from its knowledge of history; it is almost heart-searching from its knowledge of human nature; it has almost supernatural charity from its freedom from littleness and prejudice; it has almost the repose of faith, because nothing can startle it; it has almost the beauty and harmony of heavenly contemplation”. Philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre has seen this as the ability “to think about the ends of a variety of human activities” – a skill that he feels may have prevented the economic crisis, “brought about by some of the most distinguished graduates of some of the most distinguished universities”. Indeed, perhaps universities are already failing to produce the intellectual state Newman saw as crucial and, in any case, the capacity for good judgement is not limited to university graduates.

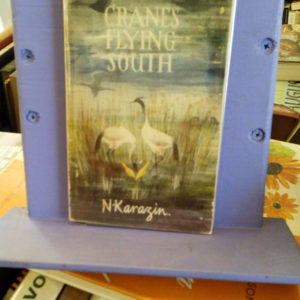

Price: R500.00

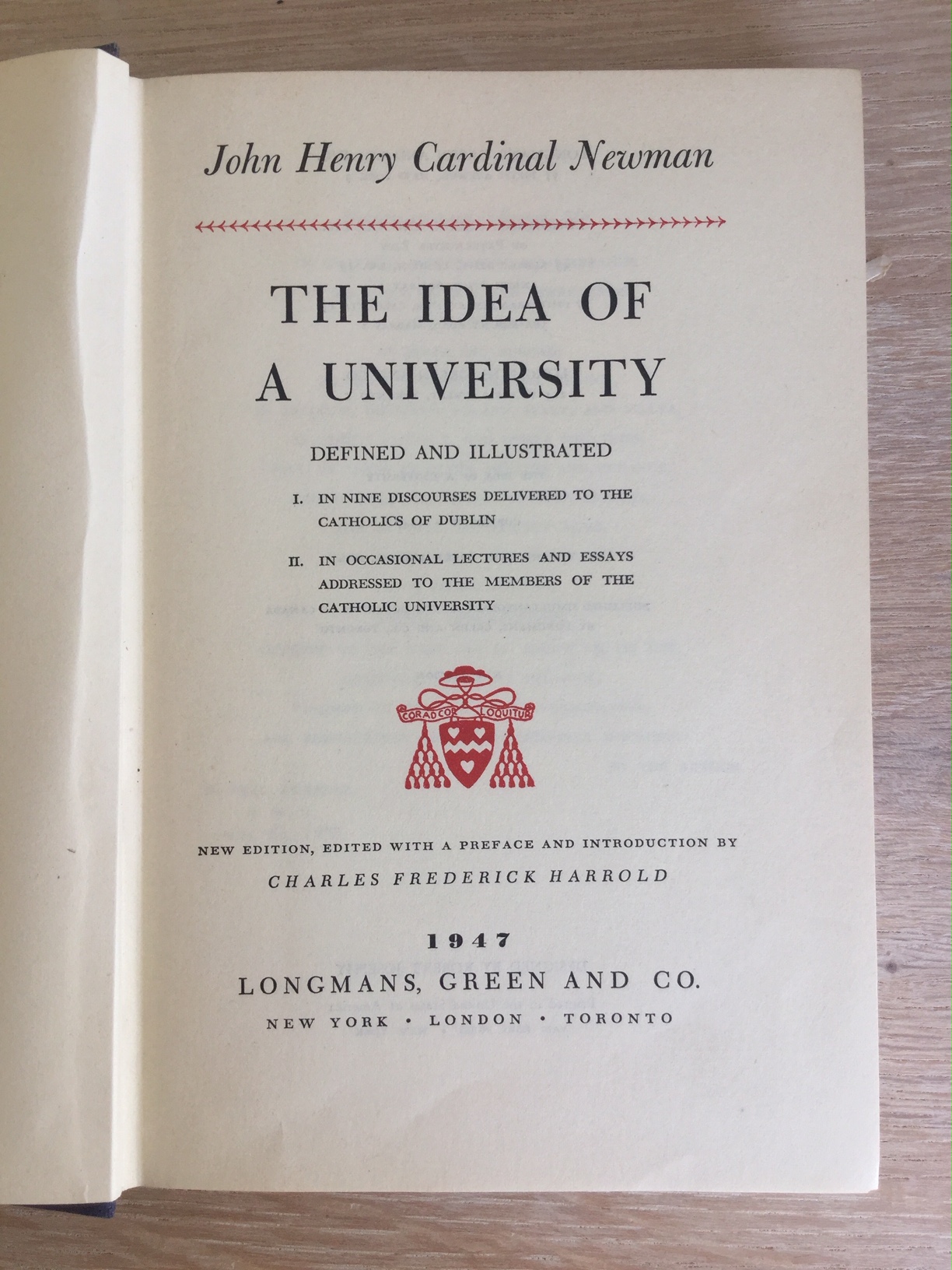

Edition: Reprint

Published: 1947

Publishers: Longmans, Green and Company

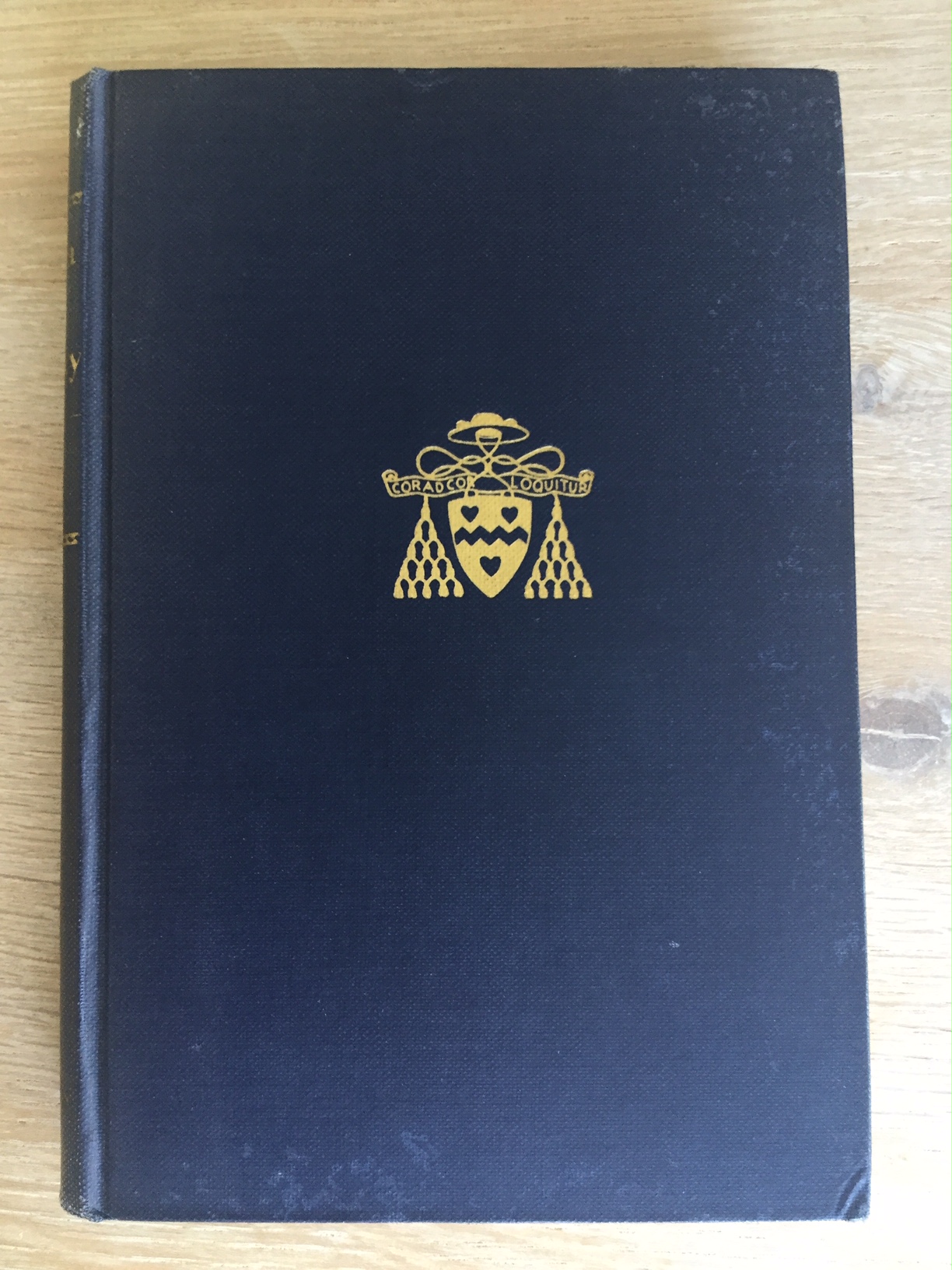

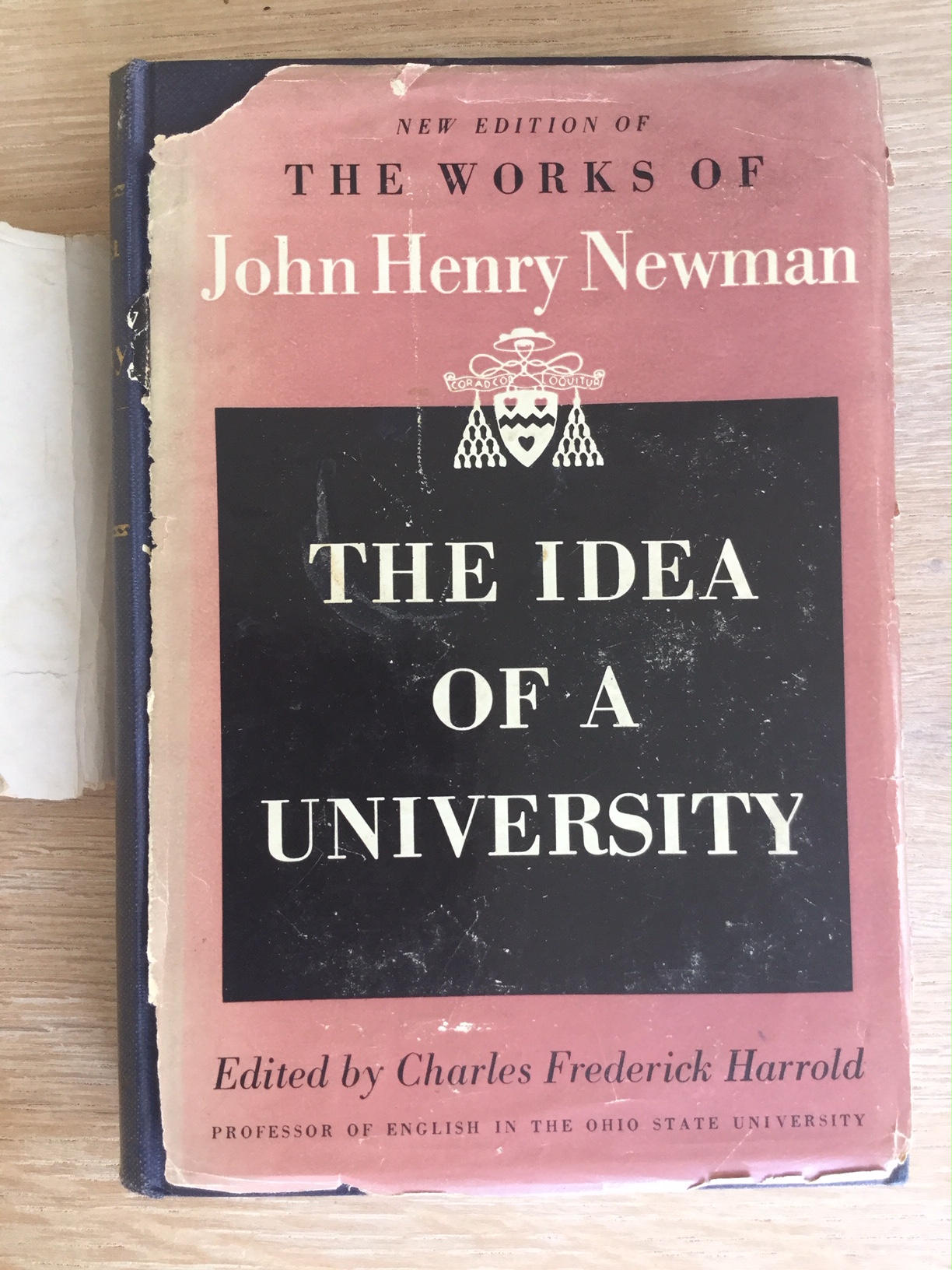

Condition: Dust jacket in very poor condition, only fit to be laminated and inserted into the copy. Cloth hardcover with gilt lettering on the cover and spine, in good condition very minor shelf wear around the edges. Internally in very good condition – very clean and tightly bound.

1 in stock

Description

For Newman, the ideal university is a community of thinkers, engaging in intellectual pursuits not for any external purpose, but as an end in itself. Envisaging a broad, liberal education, which teaches students “to think and to reason and to compare and to discriminate and to analyse”, Newman held that narrow minds were born of narrow specialisation and stipulated that students should be given a solid grounding in all areas of study. A restricted, vocational education was out of the question for him. Somewhat surprisingly, he also espoused the view that universities should be entirely free of religious interference, putting forward a secular, pluralist and inclusive ideal.

In its championing of a truly well-rounded education, this is a sympathetic vision, but there are some fundamental problems with Newman’s ideas. Despite his vision of a secular university, for Newman “religious truth is not only a portion, but a condition of general knowledge. To blot it out is nothing short … of unravelling the web of university teaching”. Knowledge alone cannot improve the individual – God, who sustains all truth, is a requirement, and this is an idea that alienates many readers.

Showing his preoccupation with man’s fallen nature, Newman wrote: “Quarry the granite rock with razors, or moor the vessel with a thread of silk; then may you hope with such keen and delicate instruments as human knowledge and human reason to contend against those giants, the passion and the pride of man.” This is an unattractively pessimistic view of humankind’s capacity for self-improvement.

Perhaps the ultimate problem with The Idea is its sheer anti-utilitarianism. Writing at a time when only an elite benefited from a university education, Newman could not have conceived of a situation where over 2 million people are enrolled at British universities and places are heavily oversubscribed. Newman says little about the level of practical, employable skills that should be imparted as part of a course of higher education, revealing his limitations as the ultimate ivory tower-dweller. He offers us little help on how the balance can be struck between pursuing knowledge for its own sake and giving students the salable skills they surely deserve. He has even less to offer on the pressing matter of how the whole enterprise may be paid for.

Newman’s approach is indeed dated, yet his articulation of the power of a university education to develop the individual in ways that far exceed the narrow limits of academic ability remains striking. Above all, Newman was arguing that the primary role of the university was to give students a “perfection of the intellect … the clear, calm, accurate vision and comprehension of all things” that allows the individual to make good judgments. He wrote of this: “It is almost prophetic from its knowledge of history; it is almost heart-searching from its knowledge of human nature; it has almost supernatural charity from its freedom from littleness and prejudice; it has almost the repose of faith, because nothing can startle it; it has almost the beauty and harmony of heavenly contemplation”. Philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre has seen this as the ability “to think about the ends of a variety of human activities” – a skill that he feels may have prevented the economic crisis, “brought about by some of the most distinguished graduates of some of the most distinguished universities”. Indeed, perhaps universities are already failing to produce the intellectual state Newman saw as crucial and, in any case, the capacity for good judgement is not limited to university graduates.

Price: R500.00

Edition: Reprint

Published: 1947

Publishers: Longmans, Green and Company

Condition: Dust jacket in very poor condition, only fit to be laminated and inserted into the copy. Cloth hardcover with gilt lettering on the cover and spine, in good condition very minor shelf wear around the edges. Internally in very good condition – very clean and tightly bound.

Additional information

| Weight | 300 g |

|---|